- >News

- >How to Tell if a Cryptocurrency is a Ponzi Scheme

How to Tell if a Cryptocurrency is a Ponzi Scheme

TerraUSD is no more. Having lost its $1 peg in the most brutal manner a week ago, founder Do Kwon announced in a tweet that the Terra blockchain will be forked into a new chain that will not feature the stablecoin, and will instead feature only LUNA as its native cryptocurrency. This means that UST has been retired, so it’s little wonder that its value is currently stagnating at around $0.09.

Prior to Do Kwon’s announcement and updates from the Luna Foundation Guard, there were online claims that Terra had effectively been a Ponzi scheme, with such speculation even predating last week’s spectacular collapse. Such claims have a ring of plausiblity about them, but with Do Kwon sticking around on Twitter to assure surviving UST holders that they will receive some compensation, it seems just as credible that Terra was simply an extremely risky financial endeavor.

A question therefore arises: how do you tell if a cryptocurrency is a Ponzi scheme? Well, there’s no easy, one-size-fits-all answer to this question, since many risky coins aren’t Ponzis in the strictest, most formal sense of the word. That said, far too many cryptocurrencies are run like Ponzis, in the sense that their growth comes only from more people speculating on them, rather than from an actual increase in organic usage.

Was Terra a Ponzi?

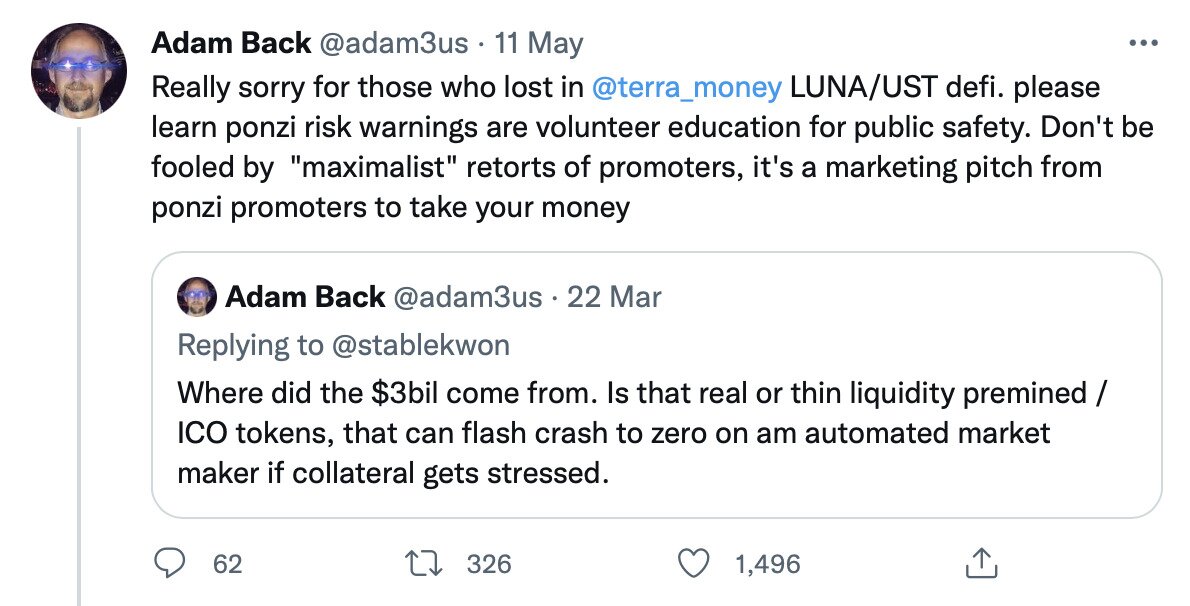

A large number of people on Crypto Twitter do seem to believe that Terra was, for all intents and purposes, a Ponzi scam. This includes such individuals as Brad Mills, Adam Back, Trader Mayne, Tomer Strolight, as well as the Singapore Police Force.

Source: Twitter

Given the confusion and lack of reliable information surrounding the collapse, plenty of rumors swirled that Do Kwon had dissolved Terra as a South Korea-based company, with an apparently official document showing that this dissolution occurred at the end of April. This was obviously a couple of weeks before the collapse, suggesting that Do Kwon and Terralabs knew about its likely occurrence.

Such claims imply that Terra may have been an intentional Ponzi, although there’s no ‘smoking gun’ evidence that really proves this beyond all reasonable doubt (and for example, Terralabs has been incorporated in Singapore since 2018). However, just because Terra wasn’t a planned Ponzi doesn’t mean it wasn’t a Ponzi-like investment vehicle.

Yes, Terra behaved very much like a Ponzi for one cardinal reason: its growth and the growth of its tokens was based solely on more people investing in it. In other words, LUNA rose in price (and UST in supply) not because more people were using it to pay for goods or services, but because it was rising in price. Likewise, LUNA wasn’t being used increasingly as the utility token of some blockchain that had real-world applications, but rather had an internal dynamic that lent itself to increasing speculation.

It’s the link between UST and LUNA that endowed Terra with Ponzi-like aspects, in that the growth of both appeared to feed into each other, despite the fact that no one was using either for anything other than speculation. For instance, Terra issued the UST stablecoin by burning LUNA, which would be used to support the price of UST whenever it dipped below $1.

This burning of LUNA was coupled with the fact that LUNA was (but is no longer) capped to a total supply of one billion. As such, it was routinely characterized as a deflationary cryptocurrency, incentivising traders to invest in it. They were also incentivised by the fact that Terra consistently increased the supply of UST, the circulation of which rose from just under $3 billion in early November to $18.7 billion before its downfall in early May.

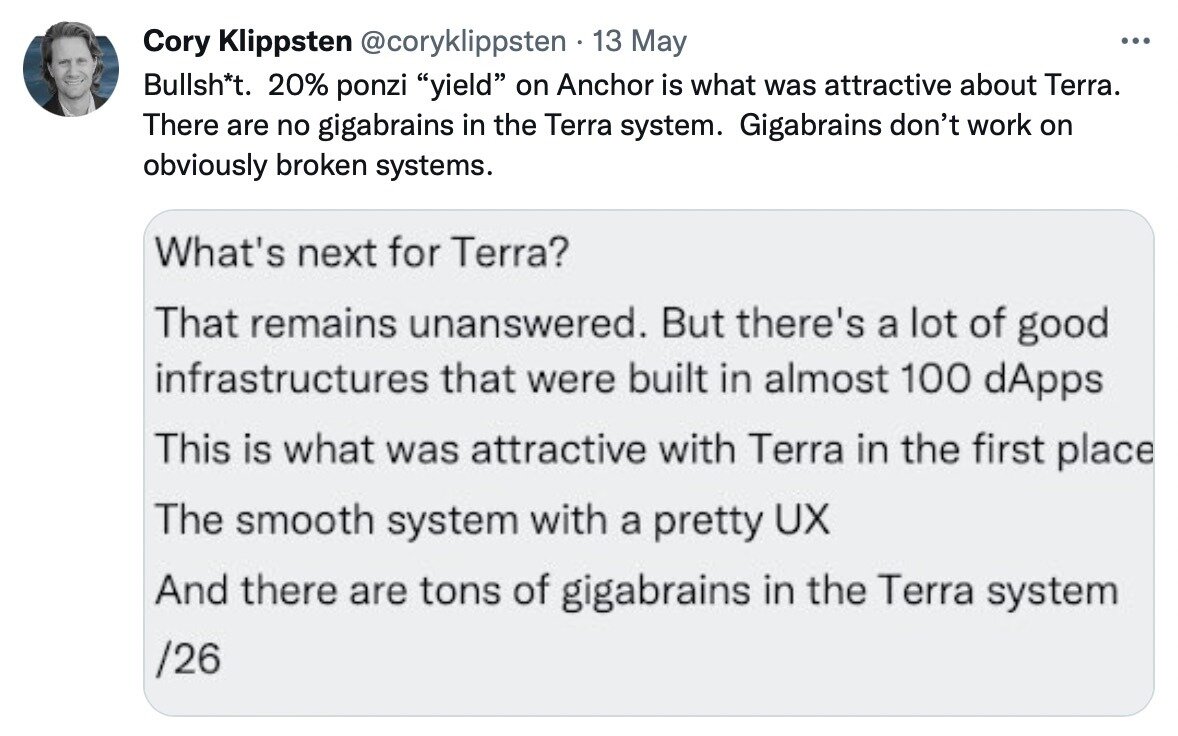

And did the supply of UST rise because of rising organic demand for it? Well, not exactly, because the main use for UST was for staking with the Terra-based Anchor protocol. At one point, Anchor was offering yields of 20% for staking UST, with Terra paying these yields by minting new UST, in a vicious circle.

Source: Twitter

The problem is, if this kind of growth doesn’t continue, the whole system can collapse, particularly during market downturns. This is exactly what happened: falling cryptocurrencies across the board also resulted in losses for LUNA, while the peg for UST was increasingly tested, dropping to $0.99 on May 7.

With holders suffering from portfolio declines, a couple of big withdrawals from Anchor caused them to panic, with a rush to sell UST quickly ensuing.

The important thing to note about UST is that it works — and attracts holders — only if it’s rising, since it has no other use or value. If it starts falling, the whole house of cards drops very quickly.

How to Tell if A Cryptocurrency is a Ponzi Scam

Terra provides an important case study on how to determine whether a cryptocurrency is a Ponzi. Of course, most cryptos probably won’t be planned Ponzis, but many may end up having Ponzi-like characteristics, particularly in terms of their internal tokenomics.

Again, the important rule of thumb to remember is this: if a cryptocurrency’s only selling point or attraction is that people are investing in it, then it’s tantamount to a Ponzi scheme. This is largely because there will be nothing to hold it up in the eventual event that it suffers a fall.

Contrary to many cryptocurrency skeptics, this basic principle rules out such major tokens as Bitcoin or Ethereum from being Ponzis. Bitcoin, for example, is witnessing increased usage among nations experiencing inflation, while Ethereum is the dominant utility chain and supports a variety of genuine use cases.

Other warning signs, as explained by the US Securities and Exchange Commission, include the following:

-

High returns with little or no risk: be suspicious of any cryptocurrency project or platform that promises consistently high returns, such as Terra’s 20% yield via Anchor

-

Secretive, complex strategies: if you can’t understand the economics or business model of a cryptocurrency, and/or find it hopelessly complex, this may be because its developers are hiding something.

-

Difficulty receiving payments: if you encounter obstacles and find it difficult to cash out from a project, be suspicious.

By considering such features when evaluating a new cryptocurrency, investors should be able to decide whether it has Ponzi-like features and is therefore a big risk. As always, do your own research.