- >News

- >Here Are The Worst Uses For Blockchain Technology Developed So Far

Here Are The Worst Uses For Blockchain Technology Developed So Far

Blockchain, not Bitcoin. Or so the saying goes, because while many within the legacy economic system seem desperate to exploit blockchain for greater efficiency or security, far too many uses of distributed ledger technology have been inconsequential at best and failures at worst.

From ‘verifying’ the wrong creator of the Mona Lisa to recording votes on untested systems, blockchain tech has been used inappropriately in an expanding range of areas. In most cases, enthusiasm for blockchain has pushed people into developing applications before they’ve seriously considered whether a blockchain could really do the things it’s supposed to do.

In commemoration of the folly of applying blockchain tech to everything, we’ve put together the four worst uses of blockchain developed to date. Regardless of whether these uses were risky or redundant, they suggest that blockchain’s real use beyond actual cryptocurrencies is more limited than many would like to think.

Blockchain ‘Verifies’ The Provenance Of Art, Food, Clothing, Etc…

Arguably the most notorious use of blockchain tech comes from 2018, when artist Terence Eden ‘verified’ himself as the painter of the Mona Lisa.

How did he do this? Well, he created an account with Verisart, a company that provides blockchain certification for artworks and collectibles. He then proceeded to upload a picture of the Mona Lisa to Verisart, while also entering his email address. That was the only ‘proof’ Verisart collected, but it was enough for the platform to declare that the Mona Lisa was henceforth “certified and verified on a decentralized public ledger.”

Source: Twitter

As Eden argued in an accompanying blog, and as others have argued before and since, a blockchain cannot prove the authenticity of anything existing outside of it. It may keep an immutable record of whatever data is entered into it, but there’s no guarantee that this data is or was accurate in the first place.

This criticism applies to blockchains that seek to track, say, the supply of fruit and vegetables or worker welfare in clothing factories.

Blockchain ‘Secures’ Digital Voting

In a world where the legitimacy of governments is increasingly being called into question, it seems that many governments are intent on doing whatever they can to increase the perception of public trust in them.

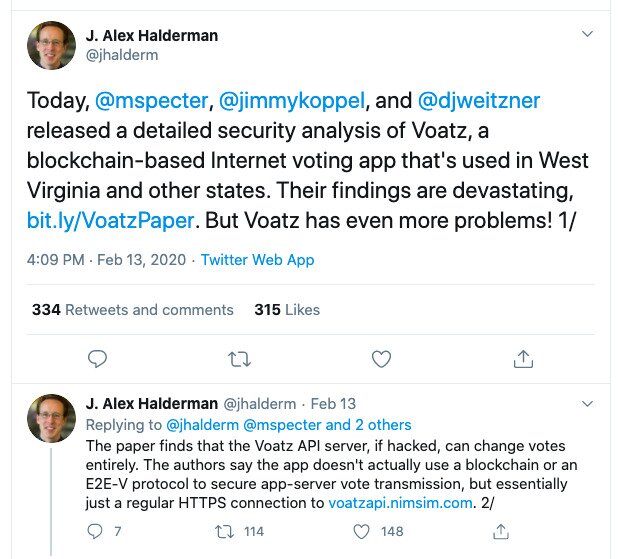

One way they’ve been trying to do this recently is by using blockchain technology with online voting. Trials in West Virginia, Colorado, Estonia, and Russia have seen online votes registered to some kind of blockchain or distributed ledger. This would theoretically prevent recorded votes from being altered, but security experts have warned that the use of blockchain brings a number of other risks.

The possibility of bugs or malware in computing systems creates the potential for votes to be changed before they’re recorded permanently on a blockchain, for instance.

Source: Twitter

Such warnings were borne out when a French security researcher calculated the private ID keys for elections in Moscow in around 20 minutes. Hacking attempts have also been made against the systems used in the United States, indicating that overconfidence in blockchain invites vulnerabilities elsewhere.

Blockchain ‘Revolutionizes’ Social Media

Social media is pretty much the defining cultural paradigm of our time, so it was all-but inevitable that more than one person would think to use blockchains to somehow change social networks for the better.

Naming all of the blockchain-based social networks conceived to data is beyond the scope of this article, but some of the most prominent include Steemit, Voice, diaspora, Minds, and All.me. Most of them revolve around two key premises: ‘paying’ users for their activity (via native cryptocurrencies), and decentralizing their networks somehow.

Neither of these really solve the major problems of legacy social media. The likes of Voice claim that paying users for content incentivizes the posting of only high-quality (and accurate) info, thereby avoiding misinformation. Yet the fact is that demonstrably false info remains surprisingly popular, as shown by how fake news was more widely shared on Facebook than ‘real’ news during the 2016 US presidential election.

This would suggest that posters of misinformation are just as likely to be rewarded as posters of fact-checked, highly corroborated information.

As for the decentralization of servers (as seen with diaspora, for instance), this may help with privacy insofar as no central company harvests user data in order to profit from it by selling ads. However, personal data is still collected, and it is likely only as secure as the platform it’s on. This can be seen with Steemit, for example, which has been hacked on more than one occasion, including most recently in May.

Source: Twitter

It’s also worth making the point that you don’t need blockchain to solve the big problems of social media. Back in 2019, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales launched WT:Social, which doesn’t use any kind of advertising and which also features moderated content.

Blockchain Makes Banking And Finance ‘More Efficient’

Finally, our last worst use of blockchain technology comes from the banking and finance sector. As with the case of social media, the involvement of blockchain is basically irrelevant to many of the solutions the banking industry is rolling out under the tag ‘blockchain.’

In April, the website Fintech News listed 10 common use cases of blockchain in banking. Aside from (cross-border) payments, ICOs, and peer-to-peer transfers (and CBDCs), all of these uses could be delivered without any kind of blockchain. These include uses related to stock exchange/trading records, trade finance records, digital ID verification, syndicated lending, accountancy, credit reporting, and hedge funds.

Source: Twitter

The idea behind most of these applications is that sharing a database between several parties reduces costs and time. This is likely true, but you don’t actually need a decentralized, immutable blockchain for this purpose.

As blockchain skeptic David Gerard noted in 2019, a blockchain is simply “a ledger you can only add new entries to — plus a ‘consensus mechanism’ to decide who gets to add new entries. That’s it.”

There’s nothing special about append-only (i.e. immutable) ledgers from the perspective of the above use cases. If a ledger shared between several parties brings any tangible benefits in the world of finance, it’s not because these parties cannot change previous entries. As such, any attempt to use a decentralized blockchain that harnesses proof-of-work consensus, or any other intensive consensus mechanism, would likely invite more costs and risks than benefits.

And in fact, it would seem that most banks and businesses are aware of this, given that only 2% of companies are currently using public, permissionless blockchains. This is a telling statistic, and ultimately, it indicates that most conceivable uses — outside of cryptocurrencies — for decentralized, public blockchains are likely ill-advised.