- >News

- >Die drei häufigsten Irrtümer zu Ethereum Name Service (und Alternativen dazu)

Die drei häufigsten Irrtümer zu Ethereum Name Service (und Alternativen dazu)

Der Ethereum Naming Service (ENS) hat seit dem letzten wichtigen Update im Jahr 2019 ein Comeback erlebt. Im Mai 2022 erreichte der Dienst mit einer Million registrierter Namen einen wichtigen Meilenstein. Dadurch büßte OpenSea seinen Status als führender Anbieter im Ethereum-Netzwerk ein.

Vor diesem Hintergrund wollen wir die häufigsten Missverständnisse zu ENS aufklären.

1. Es ist genau wie ein DNS

The Domain Name System (DNS) was invented in 1983 as an answer to the problem of having to enter an IP address in order to access a website. Entering an IP address, for eg. 127.0.0.1, is a problem because they’re difficult to remember. The DNS fixed that by allowing one to simply enter a name into the search bar, such as CryptoVantage, and it would take you to the associated IP address.

The Ethereum Name Service is not quite the same as a DNS, although one can see the similarities. When sending cryptocurrency, you have to input a wallet address. One wrong input and your crypto is lost forever, with no means of recovering it. The only exception for recovering your assets on the rare occasion when the blockchain network itself rolls back to a previous state.

The ENS aims to solve this problem by doing for wallet addresses what DNS did for web page addresses. The key difference between the ENS and DNS systems is the architecture.

The ENS architecture is non-profit, decentralised, and web3 friendly. It is also powered by Ethereum’s network. Compared to the DNS which is centralised and prone to attacks. ENS domain names are secured using smart contracts.

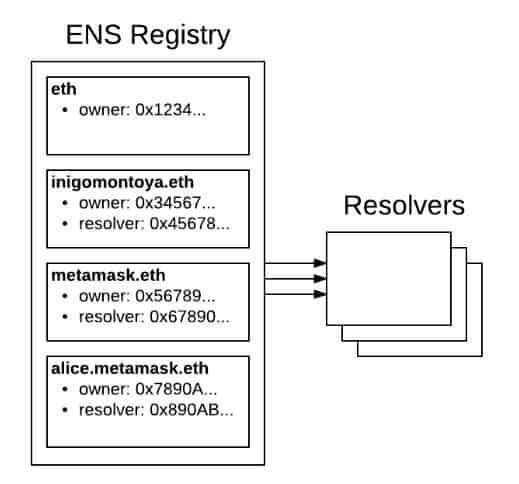

There are two main components to the ENS – the registry and resolvers.

The registry is a smart contract which maintains a list of all domains and subdomains, and stores three pieces of information about them. These are the owner of the domain, the resolver of the domain, and retrieving the time-to-live for the records under the domain.

This is how the registry can track a name to the resolver responsible for it.

Resolvers translate the names into addresses in two steps. The first being to ask the registry which resolver is responsible for a given name, and the second asks that particular resolver for the answer.

#2. ENS Has Been Around Since 2017

This is technically true but doesn’t quite get the whole story. The ENS system described above has only been around since 2019, and that is the really impressive portion of the ENS system and contributes significantly to its growth as a service in recent years.

While it is true that the ENS launched in 2017, it was quickly taken offline due to two major flaws in its code. ENS was spun up again a couple of months later in May of that same year and sales of ENS domains resumed using a Vickrey auction system.

According to a study conducted by a team of smart contract researchers, the Vickrey auction system was replaced in 2019 with the current registry system mentioned previously. In May of 2020, names registered using the Vickrey auction system were set to expire automatically if not paid a renewal fee.

In addition to ditching the Vickrey auction system, after the 2019 update, users had to pay an additional $5 fee for names that were more than six characters in length. Names under six characters did not incur fees.

After the 2019 update, more notorious brands began purchasing registry names, such as NBA and eBay. The flip side to brand-related registered names is the phenomenon of domain squatting, a form of rent-seeking behavior where users sit on a domain name that a specific brand will want and waits to receive the fees from that brand entering the market.

#3. ENS Is the Only Blockchain Name Service

ENS services aren’t the only blockchain naming services on the block. A number of services like Handshake and Namecoin have propped up competing against traditional DNS services for a number of reasons. Some common ones are the centralised nature of current DNS services, DNS security problems, and transparency concerns.

According to the handshake whitepaper, the security associated with the commonly known greenlock symbol next to secure websites is only guaranteed by a handful of centralised DNS companies. This is a major security weakpoint best highlighted by some statistics.

According to a study by Neustar International Security Council, 72% of organisations experienced a DNS attack in the past twelve months. Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) revealed the scale of a cyberattack levied against them in 2017. This particular attack was a whopping 2.5 terabytes per-second and came from 180,000 different servers, a number of these 180,000 being DNS servers.

This evidently proves the fact that DNS systems are a particularly lucrative target for would-be attackers due to their centralised nature. DNS systems from the attacker’s perspective are an easily hit single-point of failure.

With this in mind, Handshake and other blockchain naming services (BNS) seek to solve some of the problems commonly associated with DNS systems by offering a decentralised alternative. For Handshake, this is achieved with a single point of consensus associated between names and certificates, and cryptoeconomic incentives.

Concluding Thoughts: ENS Offers a Glimpse of Web3 Functionality

While DNS and ENS (and by extension, BNS) systems share a function, the means of delivering this function differ greatly.

DNS offers a centralised, Web2 version of the function which comes with its own set of pros and cons while ENS offers a decentralised, Web3 version of the function also with a set of pros and cons.

The ENS has been in existence since 2017, but only since 2019 has ENS started to gain adoption and popularity, to the point of overthrowing OpenSea as the top gas consumer on the network. Finally, ENS is not the only BNS on the block(chain). BNS systems of all stripes seek to provide a solution to the problems facing DNS systems today.